This post contains affiliate links which we are compensated for if a purchase is made. Using links costs you nothing and helps to support the ongoing creation of content. Thank you for using them.

What is the foam on top of fermenting beer? If you are new to brewing and you are making your first batch or two of beer you may have noticed the formation of foam on the surface of the brew during the fermenting process that kinda looks like the scum that forms on the surface of a spa that hasn’t been cleaned in a while. Is it something you should be concerned about?

The formation of foam at the top of your batch of beer is an entirely normal occurrence during the fermentation process. The layer, which is referred to as the Krausen, consists of yeast (alive and dead) and proteins from the wort among other things. The color of the foam is often a little unsightly being a dirty cream color that often has patches of brown gunk in it. The presence of this layer is a clear sign that the fermentation process is well underway and the brewing process is proceeding as normal.

The compounds within the Krausen itself have an extremely bitter flavor that is downright horrible to taste. It is for that reason that the Krausen should be left undisturbed at the top of the brew. If the Krausen was to be stirred into the wort there is a risk that it would affect the flavor of the finished beer. Fortunately, the vast majority of the Krausen is insoluble in water which means that it is rarely a problem.

What Happens To Krausen At The End of the Fermenting Process?

At the end of the fermentation process, you will notice that the vast majority of the Krausen has disappeared in most cases, however, it is common to see the remanence of it on the side of the vessel. The material from it coagulates and becomes denser than the wort. This results in the material sinking to the bottom of the fermenting vessel creating the characteristic sediment that is observed at the bottom of all batches.

However, there are occasions where the Krausen does not disappear and remains on the surface well after the completion of fermentation. It is believed that this occurs sometimes because a structure is created that within the foam that allows it to maintain its buoyancy. If this occurs it is best to use a paddle to poke gently. This will often result in the Krausen falling apart and sinking to the bottom.

Does The Thickness Of The Krausen Matter?

The thickness of the Krausen can vary significantly depending upon the rate of fermentation and the specific brew being made. A very thick layer of Krausen is often an indicator that the fermentation process is proceeding quite quickly as the release of a larger volume of carbon dioxide will result in an increasingly aerated foam whereas a slower fermentation will produce a thinner layer of Krausen.

The volume of the foam can also be affected by the viscosity of the Krausen which is affected by the viscosity of the wort itself. Worts with higher viscosity generally have higher surface tension or a high ability for the molecules to cling together. This property increases the capacity of the Krausen to trap the carbon dioxide gas released from the fermentation.

In some cases, the expansion of the Krausen can be so extreme that you have a blowout which is where the Krausen escapes through the airlock and onto the lid of the fermenter. This is more likely to occur when the specific gravity of the beer is higher.

The increased specific gravity is usually associated with higher alcohol contents which in turn produces more Krausen, as it is a byproduct of the fermentation process. Additionally, there is an increased volume of carbon dioxide gas that increases the chances of fermentation overflow significantly.

The probability of an overflow is also generally high in summer due to the increased temperatures which accelerate the fermentation process. This is particularly the case when the beer is one that prefers to be fermented at a cooler temperature, such as a lager.

How Prevent A Blowout Or Fermentation Overflow

There are 3 easy ways to control the volume of Krausen produced and therefore eliminate or reduce the degree of overflow. The first is the accurately control the temperature of the brew, the second is to allow adequate headspace in the vessel and the third is to use a blowoff tube which allows any escaped material to be transferred to a secondary vessel.

Temperature Control

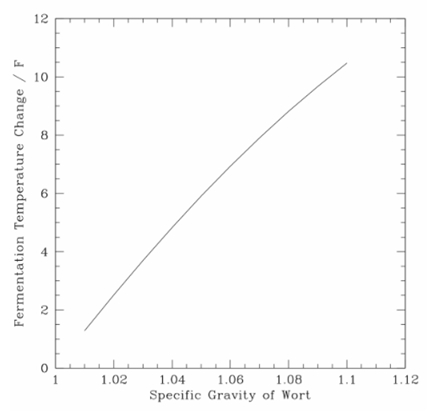

Fermentation is an exothermic process in much the same way as combustion is and as the reaction proceeds the temperature of the wort will increase. This fuelled not only by the reaction itself but also by the fact that yeast works faster at higher temperatures. A 2008 study demonstrated the relationship between wort SG and temperature increase, see the graph below.

To help manage the temperature it is advisable to start the fermentation process a few degrees below the target temperature. But if the ambient temperature is above the target temperature it may be necessary to employ some cooling techniques which could be as simple as wet cloth around the brewing vessel or the addition of ice periodically. The read more about how to control the temperature of a fermentation click here.

Leave Sufficient Headspace In The Fermentation Vessel

To avoid problems it is important to leave 20 to 30% of the volume of the headspace within the vessel. This means that a 5 gallon batch of beer should be brewed in a 6 to 6.5-gallon vessel. Avoid the temptation to overfill the vessel to get more beer.

Use An OverFlow Tube Instead Of An Airlock

Traditional airlocks can be sometimes problematic if the fermentation proceeds too quickly. This can result in the Krausen developing too quickly causing it to bubble up into the airlock and blocking it. This can cause the pressure inside the vessel to build-up in the vessel until the pressure causes the blockage to be cleared resulting in the contents of the vessel escaping.

An alternative method is to use a tube that empties into a secondary vessel this can typically be placed in the same hole that the airlock normally goes. The end of the tube needs to be submerged into a sanitary solution within the second vessel to avoid the potential for bacteria to enter the vessel.

This allows the excess Krausen to flow through the tube and into a separate vessel. As the size of the tubes is generally wider than an airlock this substantially decreases the chances of a blowout or blockage.